Collaboration between Eastman and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has led to eye-opening scientific results about how quickly certain biopolymers can degrade in seawater. Researcher Collin Ward hopes it opens eyes on other fronts too.

“We hope this pushes the Earth and environmental sciences community to think more broadly about the benefits of breaking down silos and working together,” Ward said.

Ward is a WHOI scientist who led a study to measure how quickly cellulose diacetate (CDA) breaks down in marine environments. WHOI worked with scientists from Eastman, which provided funding for the study as well as materials: CDA-based foams made with Eastman Aventa™ compostable materials.

WHOI researchers found these CDA foams, which have high surface-area-to-volume ratios, biodegrade rapidly in the ocean while also supporting circularity and material efficiency.

“With foaming, you increase the degradation rate by more than 10 times, and you get to a point where this foamed CDA is degrading faster than paper,” Ward said. “It turns out that this low-density CDA material is the fastest-degrading plastic we've ever measured in our lab, and we think it's the fastest-degrading plastic to ever be documented in the ocean.”

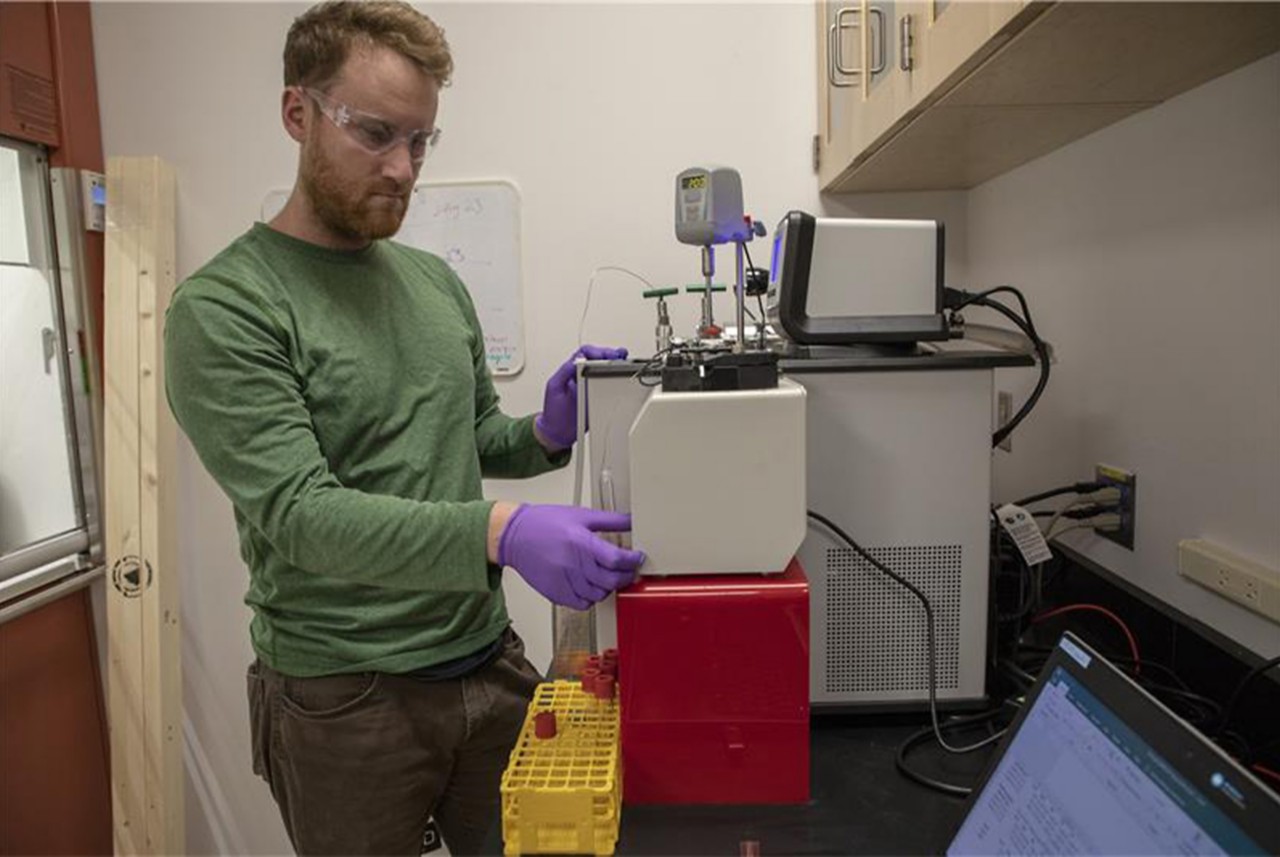

Collin Ward led the WHOI research team that studied biodegradation of cellulose diacetate.

This experiment aside, the partnership itself deserves attention. Eastman has worked for more than five years with WHOI, the world’s leading independent, nonprofit scientific organization dedicated to ocean research. Ward, who has a Ph.D. in Earth and environmental sciences, works in biogeochemistry and studies how organic molecules degrade in the environment. His previous work has produced valuable insights on degrading permafrost in the Arctic and the fate of oil during spills at sea, including the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Then he thought about translating his studies of molecular degradation to the plastic waste crisis.

“Around 2017 or so, I was having coffee with a close colleague, Christopher Reddy, another collaborator on the project, and thought, ‘Why don’t we take these tools and apply them to study the fate of plastics in the ocean?’ ” Ward said.

The partnership between WHOI and Eastman launched in January 2020. Scientists started with fundamental questions about the variables and timelines of CDA biodegradation.

“At the time, no one knew if CDA degraded in the ocean, which bugs ate it and how fast the process happened,” Ward remembered. “It was only a few years into the project when we had a firm enough grasp of that fundamental knowledge to start thinking about applying it to new products, like Aventa.”

Eastman has a century of experience in cellulosic biopolymers, which are made from sustainable wood pulp. Eastman has also studied CDAs used to produce other products, including Eastman Naia™ cellulosic fibers. The company developed Aventa as a compostable alternative for quick-service food packaging, like protein trays, cutlery and straws. Microorganisms can break down compostable food packaging that leaks into the environment so it doesn’t remain as pollution. Polystyrene foam, or Styrofoam, has long been used for quick-service food packaging, but it persists for hundreds of years in the environment.

Eastman turned to WHOI to assess how Aventa could be used as an alternative material that performs like plastic but doesn’t pollute the ocean. The results were published in 2024 in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. Eastman scientists were co-authors on the paper with Ward and his WHOI colleagues.

WHOI researcher Collin Ward

Ward was inundated with interview requests and questions from academic colleagues about the results and the academic-industry partnership. He’s happy to expound on the collaboration.

“One thing we learned over the last few years is that there's a lot of resistance to these partnerships, particularly in the Earth and environmental sciences spaces,” Ward said. He hopes this study and the results help change that. “We really push back on the narrative that all companies are just trying to buy results, and our partnership with Eastman has been the furthest thing from this. Our papers are reviewed by Eastman, but no one’s telling us what to write. No one’s telling us what questions to ask, what hypotheses to test or how to interpret the data. We work amicably together to translate fundamental science into useful and more sustainable materials. It’s been one of the more gratifying collaborations of my career.”

Ward said big challenges need translational science that can be scaled up to make a real impact. Problems like plastic waste need the combined expertise of academic and industrial science.

“We think that bringing academia and industry together can solve this problem faster,” Ward said.